Vor 130 Jahren war hier nichts und niemand. Es gab keinen Grund dort zu leben, wo sich jetzt Wellblech an notdürftig gemauerte Hütten reiht, wo die Straßen holprig, aber dafür belebt sind. Doch 1886 wurde im Nordosten von Südafrika eine der größten Goldadern der Welt entdeckt, die Region wurde Gauteng – Zulu für „Stadt des Goldes“ – genannt, die burischen Siedler ließen sich nieder. Johannesburg war geboren, und das Gold lockte Arbeiter, Goldgräber aus dem ganzen Land in die einst menschenleere Hochfeldlandschaft. Wo aber sollten sie wohnen? Townships nannte man die einfachen, aus dem Boden gestampften Arbeitersiedlungen in denen Neuankömmlinge auf dem Boden schliefen, bevor sie sich nach und nach eine Wellblechhütte erkämpfen konnten.

Noch heute kann man zwei alte Minentürme nahe der Innenstadt besichtigen, doch die Goldader, der einzige Siedlungsgrund in Johannesburg, ist quasi versiegt. Aber nach wie vor hat Johannesburg den Ruf einer Goldgräberstadt: Wo es früher um ein Edelmetall ging, geht es heute um eine vermeintliche Fülle an Jobs, an Gelegenheiten, Geld zu machen. Und dieses ewige Wachstum sorgt dafür, dass Johannesburg heute mehr als 4 Millionen Einwohner zählt – ganz genau weiß man das nicht. Etwa die Hälfte von ihnen lebt dort, wo wir heute den Tag verbringen: In Soweto.

Soweto – der South Western Township in Johannesburg

Die Viertel, die wir auf der Fahrt nach Soweto durchqueren, gab es vor zehn Jahren noch nicht, Soweto selbst allerdings schon. Die Southern Suburbs, zu denen auch der South Western Township gehört, sind heute der Siedlungsbereich Johannesburgs mit den meisten Einwohnern. Zwar macht er nur ein Zwanzigstel der Stadtfläche aus – aber über 2 Millionen, also gut die Hälfte der Einwohner, leben hier. 1 Millionen Johannesburger verteilen sich auf die Northern Suburbs – dort, wo früher nur Weiße erlaubt waren und bis heute nur sehr einkommensstarke Südafrikaner leben. Das Stadtzentrum mit seinen 300 oder 400.000 Einwohnern gilt für uns weiße Touristen auch heute noch als Tabuzone. Nicht aber Soweto.

Erst seit 60 Jahren Jahren hat das Township einen eigenen Namen, seit 12 Jahren ist es offiziell ein Teil von Johannesburg. Wenn man die für die Fußball-WM angelegte Ivory Avenue mit ihren Straßenlaternen in Form von Elefantenzähnen entlangfährt ahnt man, dass Soweto längst nicht mehr das ist, für das wir es halten. Wellblechhütten? Ja, immer noch, aber eben auch Steinhäuser mit Vorgarten, mit doppelt verglasten Fenstern und einem hippen Café ums Eck. Die Weltmeisterschaft war auch abseits der Ivory Avenue nachhaltig gewinnbringend für Südafrika: Es gibt so viele Investoren wie nie zuvor, die Besuchergrenze hat die 10 Millionen-Grenze nie wieder unterschritten, das FNB Fußballstadion – das Hauptstadion der WM – wird als fast einziges WM-Stadion noch heute viel genutzt.

Aber zurück zur Realität, zur breiten Masse. Geschätzte 50 % der Einwohner sind arbeitslos. Die Mär vom grünen Gras auf der anderen Seite, vom saftigen Arbeitsmarkt in Johannesburg, hat sich in ganz Südafrika herumgesprochen; kommen die Menschen in Soweto an, sind sie ernüchtert. Das Gras ist grüner, ja, aber es wächst hinter den Zäunen der Reichen in den Northern Suburbs. Zehntausende Neuankömmlinge leben tatsächlich noch in Blechhütten ohne Strom. Und trotzdem ist die Kriminalität in Soweto geringer als in vielen anderen Teilen des Landes, der Stadt sogar. Betteln ist verpönt, jeder Bewohner sucht sich seine Aufgabe, seine Möglichkeit, irgendwie Geld zu verdienen: Als Reifenhändler, als Friseur, mit Wasserkanistern, Kochtöpfen oder dem Bierverkauf aus dem eigenen Fenster. Man hält sich über Wasser. Man hilft einander. Man respektiert den Erfolg des anderen, einzig aus dem Glauben heraus, dass Erfolg aus harter Arbeit resultiert – und folglich verdient ist.

Und man glaubt an Ubuntu – das ungeschriebene Gesetz, dass der Einzelne nur durch die Gemeinschaft eine Chance zur Verbesserung seiner Situation hat.

Man sieht auf den ersten Blick, wer ein Black Diamond ist in Soweto, einer derjenigen, die es geschafft haben: Sie haben ihre Elternhäuser – einfache Wellblech- oder Holzhütten – in kleine Stadthäuser umgebaut, vor der Tür steht ein Auto. Die Erfolgreichen ziehen nicht weg, warum auch? Ihnen droht keine Gefahr, nur selten wird eingebrochen. Die Menschen wissen, dass sich auch ihre Lebenssituation durch den Erfolg des Nachbarn verbessern wird, weil er seine Reifen weiterhin bei ihnen kauft. Und das tut er, allein schon aus Stolz. Die Menschen in Soweto schauen nacheinander, das merkt man an jeder Ecke. Jede Straße ist ein kleines autarkes System für sich: Es gibt Tauschgeschäfte, Geld fließt wenig, schneidest du mir die Haare, bekommst du deine fünf Flaschen Bier morgen umsonst. Die Kinder spielen auf der Straße, mal bei Delani, mal bei Sifise. Jeder weiß genau, wo sie hingehören. Es passiert nur wenig, seit sich Menschenrechte hier wirklich Menschenrechte nennen dürfen.

Wir machen Halt an den Orlando Towers, einem 1982 stillgelegten Kohlekraftwerk, das heute als Wahrzeichen Sowetos gilt. Kein Wunder: Man sieht die Türme vom gesamten Township aus. Die FNB Bank hat in einem schlauen Marketingzug den rechten Turm als riesige Werbetafel gewonnen indem sie sich verpflichtete, den linken Turm zum größten Kunstwerk Afrikas zu machen. Heute kann man mit einem Aufzug an den bunt bemalten Türmen hochfahren, Bungeejumps und Freefall-Sprünge machen. Am Fuße der beiden Türme liegt die wohl coolste Bar Südafrikas, das Chaf-Pozi. Hier ein Castle oder ein Lion Beer trinken, das steht ebenso auf der Liste fürs nächste Mal wie der Bungee Sprung zwischen den Orlando Towers.

Aber jetzt bleibt keine Zeit – wir sind verabredet in Orlando East. Wir bringen gemeinsam mit unserem Freund Karsten, der in Südafrika aufgewachsen ist und in Johannesburg lebt, Klamotten, Spielzeug und Essen zu einigen Familien in einem der bekannteren Stadtteile Sowetos und dürfen dafür einen Einblick in ihre Wohngemeinschaft erhalten. Und ich kann nicht sagen, wann ich das letzte Mal so herzlich, so offen in Empfang genommen wurde.

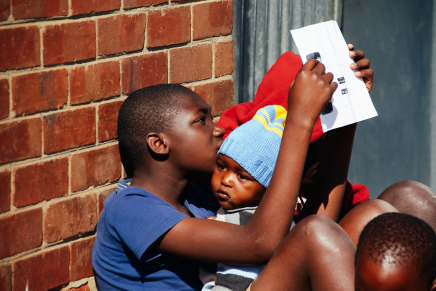

So schüchtern die Kids anfangs sind, so breit grinsen ihre Mütter, als wir den Innenhof einiger Wellblechhütten betreten. Räumen schnell auf, bevor wir ihre fünf Quadratmeter Privatsphäre betreten, die sie sich zu dritt, manchmal zu viert teilen. Hier hat alles seinen Platz: Auf der Mikrowelle stapeln sich einige Plastikteller: Die Küche. Auf der Holzleiste daneben stehen in Reih und Glied Kosmetika: Das Badezimmer. Ein Eimer Wasser steht neben der Tür, auf dem schmalen Bett liegt der fünfjährige Ayize und schaut mich neugierig an. Wenig später klebt er an meiner Seite, als ich ihm die Bilder von ihm und seinen Freunden auf dem Kameradisplay zeige.

Was ich gelernt habe in Soweto: Dass die Schule kostenlos ist – aber die Eintrittskarte eine Schuluniform, und daran mangelt es in den meisten Fällen. Dass die Liebe und die Fürsorge groß ist – aber dass sie keine hungrigen Mägen füllen können. Dass Grundlagen geschaffen wurden – auch die medizinische Betreuung jeglicher Art ist hier übrigens gratis – aber dass die Ressourcen knapp sind. Kranke müssen oft tagelang auf eine Behandlung warten, wenn sie es erstmal ins Krankenhaus geschafft haben; hunderte, wenn nicht tausende Kinder dürfen nicht lesen lernen, weil sie sich keine Uniform leisten können. Schlicht zu viele Menschen wollen nutzen, was ihnen seit dem Ende der Apartheid endlich erlaubt ist. Diese Stadt ist voller Möglichkeiten, aber sie ist von sich selbst überfordert.

Must Sees in Soweto

- Das Nelson Mandela Haus ist der Klassiker und definitiv einen Besuch wert: Mandela wurde weder hier geboren, noch starb er hier, doch für ihn selbst war das Haus in der Vilakazi Street in Orlando West (in der übrigens auch Bishop Desmond Tutu bis vor acht Jahren gelebt hat) definitiv das Zentrum seines Lebens.

- Das Apartheid-Museum ist eines der Museen, in denen man problemlos die Zeit vergessen und einige Stunden verbringen kann. Unbedingt Kopfhörer ausleihen und sein eigenes Tempo finden!

- Das Hector Pieterson Memorial mit seinem Museum ist einer der bewegendsten Plätze in der Geschichte der Apartheid und wird leicht links liegen gelassen. Die Geschichte dahinter hat mich sehr bewegt.

- Das Sakhumzi Restaurant in Orlando West gilt als die Institution, wenn es um authentische südafrikanische Küche geht: In knapp 20 Töpfen schmoren lokale Speisen vor sich hin, es riecht köstlich.

- Schräg gegenüber liegt das Thrive Café, in dem eine von drei original italienischen Kaffeemaschinen in Johannesburg steht und das vom Stil her auch irgendwo in Europa stehen könnte.

- Kinderlächeln, wenn man mit vollen Händen kommt, auch wenn es sich nicht um Chips und Spielzeug handelt. Es gibt diverse Anlaufstellen für Sachspenden und es empfiehlt sich, sich an eine lokale Organisation zu wenden statt wahllos zu verteilen. Per Email kann ich gerne Kontakte vermitteln. Wer von hier aus in ein weiteres Township Johannesburgs spenden will, kann das zum Beispiel bei unserem Help Alliance Projekt Safe House tun.

- Das echte Leben, fernab von Touri-Bussen. Wir haben unsere Tour durch Soweto mit Freund und Tourguide Karsten gemacht – auf Anfrage kann ich gerne vermitteln. Obwohl es nicht gefährlich ist, würde ich Touren auf eigene Faust nicht empfehlen, allein schon weil dann so viele wichtige und spannende Informationen verloren gehen. Auf alle Fälle solltet ihr darauf achten, nicht in einen der furchtbaren Touribusse zu geraten, die durch Soweto fahren, kurz halten um ihren Insassen Fotos aus dem Fenster zu ermöglichen und dann wieder weiterfahren. Ihr verpasst so viel, wenn ihr das tut.

130 years ago, noone and nothing lived here. There was no reason to settle where today, tin huts and bumpy streets are buzzing with people. But in 1886, one of the biggest gold veins in the world was found in the North East of South Africa, the region was named Gauteng – Zulu for „City of Gold“ – and the Boer settled down. Johannesburg was born, and the gold attracted loads of workers, gold miners from all over the country into the once deserted upfield region. But where to live? Townships was how they called the simple, made-of-nothing working-class quarters, where newcomers slept on the floors until they finally managed to eke out a hut of their own.

Until today, you can visit two old gold mines close to the city center, but the gold vain, the only reason for settling in Johannesburg, has run dry. Still, the city has the feel of a booms town. It used to be gold that attracted people, now it is the myth of a prospering job market. More and more people from the country keep moving into Johannesburg, and this ongoing growth is why today, it has more than 4 million inhabitants. And about half of them live where we are heading today: In Soweto.

Soweto – the South Western Township of Johannesburg

The quarters we drive through on our way to Soweto weren’t even there about ten years ago. The South Western Townships were. The Southern Suburbs are today Johannesburgs most populated part: Though it only makes up a twentieth oft he city area, more than 2 million, a good half of the inhabitants, live here. 1 million people spread over the Northern Suburbs – where not too long ago, only the white population was allowed and up to now, only the wealthiest of the South Africans live. The downtown area with its 300 or 400.000 inhabitants is still a tabooed place for us white tourists. Soweto isn’t.

Only since 60 years, the township has its own name, since 12 years it is officially a part of Johannesburg. Driving down Ivory Avenue with its street lights formed like elephant’s teeth, constructed for the world championship 2010, you can tell that Soweto is no longer the slum we think of when we hear its name. Tin huts? Yes, but alongside stone houses with tiny front gardens, double-glazed windows and a hip coffee place around the corner. The championship was profitable for the country in many concerns: There are more investors than ever, the visitor count has never fallen under 10 millions again, the FNB football stadium – the main stadium oft he championship – is one of the few championship stadiums that is still frequently used.

But back to reality, back to the rank and file. Roughly 50 % of the inhabitants are jobless. The fairy tale of the green grass on the other side, of the juicy job market in Johannesburg, has spread over whole South Africa; once people arrive in Soweto, they are disillusioned. The grass is greener, yes, but it only grows behind the fences of the rich in the Northern Suburbs. Ten thousands of newcomers still live in the well-known tin huts without any electricity or running water. And still, the crime rate in Soweto is lower than in many other parts of the country, the city even. Begging is frowned upon, every inhabitant finds his function, his individual way to make money: As a tire dealer or a hairdresser, selling beer from the window sill or water canisters. They scratch a living. They help each other out. They respect the success of the other, if only due to the belief that success is the payoff for hard work – and thus deserved.

And they believe in Ubuntu – the unwritten law that the individual can only improve his situation as part of the community: A person is a person through other people.

You can tell from afar who is a Black Diamond in Soweto, one of those who made it: They have rebuilt their parents houses – simple tin huts or wooden shacks – into little town houses, a car waiting on the doorstep. The successful don’t move away, why would they? There is no hazard, burglary is rare. People know that the success of their neighbor will eventually improve their own position, because they know he will keep buying his tires and his beer from them. And he will. The people of Soweto look after one another, you can feel it on every corner. Every street is its own self-sufficient system: A lot of barter business, almost no cash, if you cut my hair, your next beer is on me. The kids are playing in the streets, one day at Delani’s, the next day at Sifise’s place. Everyone knows who belongs where. Not much is happening here, now that the human rights finally live up to their name.

We make a stop at the Orlando Towers, a closed-down power plant which is now the town’s landmark. You can see the two towers from the whole town. The FNB bank made a smart move gaining the right tower as a huge billboard by turning the left one into Africa’s biggest piece of art. Today, you can get up on the towers in an elevator, do bungee jumps and freefall jumps from up there. At the feet of the towers, you can find the supposedly coolest bar of South Africa: The Chaf-Pozi. Drinking a Castle or a Lion Beer here is on my list for the next visit, followed by jumping off the towers with a rope around my hips.

But now, there’s no time – we have a date in Orlando East. Together with our friend Karsten, born and raised in South Africa and living in Johannesburg, we bring clothes, toys and food to a few families in one of the well-known areas of Soweto and therefore get the chance to catch a glimpse into their community. And I can’t remember being welcomed into a group this warmly ever before.

As shy as the kids are in the beginning, as broad do the mothers grin when we walk into the yard between their huts. They hurry to clear up their family’s five square meters of private sphere before they invite us in. In here, everything has its place, that’s the only way it works: A few plastic plates pile up on the microwave – the kitchen. Cosmetics are arranged neatly on the strip of wood next to it – the bathroom. A bucket of water is placed next to the door, five year old Ayize is watching me warily from the narrow bed. Minutes later he clings to my side when I show him the pictures I took of him and his friends on my camera’s display.

What I learned in Soweto: School is for free here – but the entrance ticket is a school uniform most families can’t afford. There is a lot of love in these houses and huts – but love can’t buy neither food nor clothes. The groundwork is built – even the medical care of any kind is complimentary – but the capabilities are scarce. The ill often have to wait for hours and days until they can be treated, once they finally made it to the hospital; hundreds, if not thousands of kids can’t learn to read because their parents can’t afford a uniform. There are simply too many humans who want and need to do what, with the end of apartheid, they finally are entitled to. This city is full of possibilities, but it is swamped by itself.

Must Sees in Soweto

- The Nelson Mandela House is the classic destination of all tourists coming to Soweto and definitely worth a visit: Mandela was neither born nor did he die here, but he himself described the house in Orlando West’s Vilakazi Street (also being the home of Bishop Desmond Tutu until eight years ago) as the centre of his life.

- The Apartheid-Museum is one of those museums in which you can easily lose track of time and spend hours in. Do get the headphones and move at your own pace!

- The Hector Pieterson Memorial with its Museum is one of the most moving places in the history of Apartheid and is easily missed – try not to! The history behind it moved me a lot.

- Sakhumzi Restaurant in Orlando West seems to be the place to go for authentic South African cuisine: Around 20 pots spread the delicious smell of local dishs.

- Just accross the street we find Thrive Café, which has one of just three Italian coffeemakers of Johannesburg – and which, in appearance, might as well be located somewhere in Europe.

- The smiles of Soweto’s children when you arrive with full hands, even if it’s not sweets and toys you’re bringing. There are a lot of places to bring donations of any kind and I definitely recommend getting in touch with those instead of randomly handing out stuff – let me know if you need me to hook you up with someone via mail.

- The real life, far off of tourist busses. We did our tour through Soweto accompanied by our friend and tour guide Karsten – let me know if you want to do the same. Even though it’s not per se dangerous, I would not recommend to go on your own, if only because you miss out on so much information. And please, please don’t get on one of those tourist busses driving through Soweto, making nothing but short photo stops. Soweto is worth your time!

Pingback: Bungee Jumping in Johannesburg: Soweto von ganz weit oben | Helle Flecken

Pingback: New Year’s Outfit: Be fierce or go home! | Helle Flecken